Earth

Kendra Klein: Reducing Exposure to Pesticides, a Scientifically Proven Way

On today’s episode of Rootstock Radio, we’re chatting with Kendra Klein, senior staff scientist at Friends of the Earth (FOE) and a seasoned writer, researcher and advocate (Kendra’s been at this kind of work for a full 17 years!). Kendra shares what that FOE is doing to change our food and agriculture system for the better.

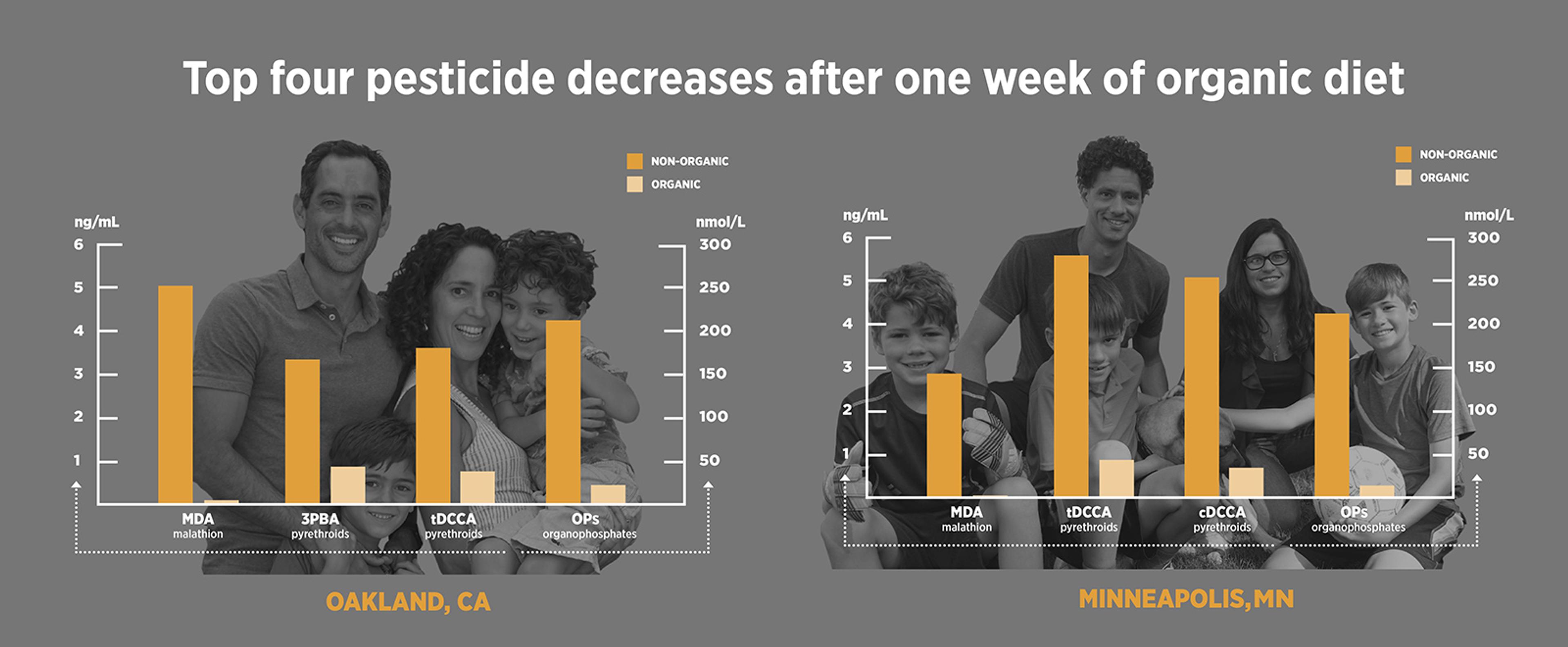

Their most recent news is the release of an exciting new study that found switching to organic food can dramatically reduce your exposure to pesticides—we’re talking drops of 60% in just 6 days, and up to 95% depending on the compound! The study also found 14 specific pesticides in every single participant (a fact that should thoroughly alarm us all).

The hopeful news is that this study, and others like it, shows it IS POSSIBLE to seriously reduce the amount of pesticide residues in our bodies through our diet. And in a world where a lot of things feel completely out of our control, our food choices are something that’s still in our own hands. View the study’s summary video below, and read more about the peer-reviewed study here at Organic for All.

Hear Kendra Klein at the link below, on iTunes, Stitcher, Google Play, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts.

Rootstock Radio Interview with Kendra Klein

Air Date: April 8, 2019

Welcome to Rootstock Radio. Join us as host Theresa Marquez talks to leaders from the Good Food movement about food, farming, and our global future. Rootstock Radio—propagating a healthy planet. Now, here’s host Theresa Marquez.

THERESA MARQUEZ: Hello, and welcome to Rootstock Radio. I’m Theresa Marquez, and I’m here today with Dr. Kendra Klein, who is the senior staff scientist at Friends of the Earth, where she leads work on food and farming solutions. Kendra is also a writer, a research[er], and advocate. She’s written just a lot of different wonderful articles about food and farming, and actually been doing this for 17 years. Kendra, thank you so much for joining us today.

KENDRA KLEIN: Thank you so much, Theresa.

TM: I am extremely eager to discuss the new study that you have been shepherding on the organic diet. But before we do, I think I want to make sure our listeners know all about the Friends of the Earth. I just was going through the three things that FOE, which is a lot of what we call it—certainly people understand FOE is not a bad acronym for an organization that wants to be “a bold and fearless voice,” fight for systemic transformations in our food and agriculture, and they want to organize and build for long-term change in power around the areas of social justice [and] environmental justice. And I should ask you, Kendra, how old is FOE now?

KK: Friends of the Earth was founded in 1969 by David Brower, and our Food & Agriculture program is just five years old. We’re doing great work on pollinator health, so a lot of work on reducing pesticide use and improving the health of our food systems for pollinators. And we know that pollinators are really like the canaries in the cornfields. The fact that we are losing mass amounts of bees and butterflies also tells us that the way we’re farming, the dominant way we’re farming is on a fatal track for us as well. What we do to the environment we do to ourselves. So we’re doing a lot of work on pesticides, work on GMOs, on regulation and public education, and working with leading companies. We do work on fisheries and sustainable fishing in oceans, and also a lot of work to reduce industrial style meat and to promote the pasture-raised and sustainable and organic meat and dairy production.

TM: Well, that’s a heck of a large agenda, and how appropriate for Friends of the Earth. And you know, for 17 years you actually have been working in this sphere of sustainable ag. And I was just reading about you worked around Health Care Without Harm and also with Breast Cancer Action. What do you think: how did this prepare you for the kind of work you’re doing now with Friends of the Earth?

KK: Well, I started out working at Breast Cancer Action because my mom was diagnosed with breast cancer when I was two and then again when I was twenty. And that really inspired me to think about environmental links to cancer and what are we being exposed to and the increasing use of toxic products in so many of our consumer products and also pesticides. So that really was the beginning of my introduction to human health concerns related to pesticides.

And I did that work for a number of years and got really interested in how do I turn my energy towards the solution? And went and apprenticed on organic farms in Hawaii and California and learned about how we can grow food without the use of toxic pesticides. And ever since then I have been bringing together those two interests in human health and the way that our health is really embedded in the health of the environment, and pursuing solutions around organic and ecological farming.

TM: Well, you know, Kendra, it is so heartening to hear that you actually went to a farm and worked. How do you think it changed the way that you look at the kind of work you do?

KK: I’ll say particularly the farms I was on in Hawaii were just phenomenal in terms of incredible ecological practices and what they were able to accomplish working with the environment. At the same time, they were struggling financially, and so it really led me to the question, how do we scale up sustainable agriculture in a way that really works for farmers and works for all of us? And that led me to graduate school.

That’s when I got involved with Health Care Without Harm, because my research focused on institutional procurement of sustainable food. Because you and I can go to the farmers’ market and we buy two or three onions, but a hospital, when they are buying onions, they’re buying them by the case and they’re making 70 pounds of soup at a time. And so when they start shifting their food dollars, that can have a real ripple effect in the food system. And so I worked with Health Care Without Harm and designed my dissertation research around that question of how do we scale up and how do we get these really big buyers to be able to plug into some of the most exciting shifts in our food system toward sustainability and health.

TM: Let’s fast-forward a little bit. The new Friends of the Earth organic diet study that just was released, was it two or three weeks ago? Tell us about it!

KK: Yeah. So this is a couple years in the making. We were inspired, if anybody has seen a video that came out of Sweden, where they took a family, put them on an organic diet for a week, and all of the pesticides they found dropped dramatically. And it turned out there’s also peer-reviewed studies that back this up. There’s now four and ours is the fifth peer-reviewed study that shows that switching to an organic [diet] can rapidly and dramatically reduce your exposure to pesticides.

What we found is everything dropped up to 95 percent after just six days on an organic diet. So we first found four families across the country. We found racially diverse families so that many of us can see ourselves reflected in this research. And we’re really grateful to our partners on the ground. We worked with MOSES to find a family in Minneapolis; with Georgia Organics to find a family in Atlanta; with Maryland Pesticide Education Network to find a family in Baltimore; and then we also found a family in Oakland. And we found folks who had not historically eaten organic food, and we switched out their whole diet, all the way down to oils and spices. We had research assistants do their shopping for them, and licensed chefs who made their dinners, just in case they got real busy one night and weren’t able to prepare an organic meal.

So it was six days on a purely conventional diet, six days on purely organic, and they gave us a urine sample every morning—all families with kids. And we worked with laboratories at UC–San Francisco and the Quebec National Institute of Public Health. And they found 14 different pesticide compounds in all of the people we tested. And those include some pesticides that we’re really concerned with in relation to people’s health, so organophosphates; people may have heard of chlorpyrifos that has been in the news lately. EPA scientists have determined that there’s no safe level of exposure to chlorpyrifos and was set to ban this pesticide, but one of the first things the Trump administration did when they came into office was reverse course on that ban. So this is something we found in all of our participants, and after just six days on an organic diet it dropped 61 percent.

(9:08)

TM: That is so very exciting. But perhaps maybe we should back up just a little bit and talk a little bit about the current evidence that shows what are the problems with being overly exposed to pesticides.

KK: That’s a great question. So for the general population, the way that we’re most exposed to pesticides is through the food we eat. And what we know is that small exposures matter. And that’s because even if all of the pesticide residues on our food are below legal limits—and they do tend to be; when the USDA tests for food residues, they typically find that residues are below legal limits.

TM: You know, just to get clear, you were testing for, as you said, more than just glyphosate, more than just one pesticide.

KK: Right. This is why we’re concerned about people’s dietary exposure, because cumulative exposures add up. And so what we see in our study is a snapshot of a cocktail of pesticides that people are exposed to in their daily diets. So we found organophosphates, pyrethroids, a neonicotinoid, and the herbicide 2,4-D. So, with each meal, for most of us, eating conventional food, we’re having that daily exposure. And the legal limits for pesticides are set one by one, and they’re not accounting for the fact that we are having cumulative exposures and that there are additive and synergistic impacts. The latest science is showing us that certain combinations of pesticides we’re exposed to can actually increase the potency of some of those pesticides.

And the other thing we’re learning, we used to think the dose makes the poison and that there might be a safe dose of most given chemicals or pesticides. But what we increasingly understand is that incredibly small exposures to pesticides and other industrial chemicals can disrupt our hormone systems. They can scramble and block and mimic the hormonal messages that our bodies are using to regulate our metabolism, our reproductive systems, our immune systems. And so even incredibly small exposures can have significant and concerning impacts. And we’re most concerned about children and infants and babies in utero because they’re developing so rapidly that small exposures during those windows of development can have lifetime impacts.

TM: Well, you know, there’s been three decades’ worth of research and observations. I’m thinking even for 1990, but during 1990, I think ’97 is when Theo Colborn published Our Stolen Future. And I know that your study certainly should open the doors to looking at change in policy, change in Farm Bill subsidies, and so on. Why are we being so reckless, or, you might say, gambling with this? What do you think this study can do to help us push us into better policy?

KK: At Friends of the Earth we follow the money on so many issues related to why we’re not making change for human health and for the environment. And when it comes to pesticides, the pesticide industry is expected to top $330 billion in profits by 2021. So there are some deeply entrenched economic interests that continue this toxic business-as-usual. They’ve got lobbying power and they’ve also got messaging power. So we did an analysis called “Spinning Food” that demonstrates that they’ve really taken a page from the tobacco playbook and have invested tens of millions of dollars each year in disinformation campaigns that paint pesticides as safe and that undermine people’s understanding of the benefits of organic.

And that’s really important for policy makers to understand the science and understand that organic is a real solution. That’s what’s so exciting, is we’ve got the solution, and that’s what our study shows, is that this is possible. And we know, from all of the successful organic farmers out there, that this is possible as a farming solution and as a solution for our health and for the environment. So at Friends of the Earth we are working with many allies to shift that system and shift our support and our subsidies and our incentives away from a pesticide-intensive system to an organic and ecological system.

(14:20)

TM: If you’re just joining us, you’re listening to Rootstock Radio, and I’m Theresa Marquez. And I’m here today with Dr. Kendra Klein, senior staff scientist at Friends of the Earth. Kendra, tell us, what is the official name of the organic diet study?

KK: So the study was published in the journal Environmental Research, and the official name is “Organic Diet Intervention Significantly Reduces Urinary Pesticide Levels in U.S. Children and Adults.” And you can actually find that—it’s open access. So if you scribble that down and search for it, or you can go to OrganicForAll.org and just click on the study in the menu, and you will find a link to that study. And I also want to give huge thanks to the co-authors on the study. We worked with researchers at UC–Berkeley, at UC–San Francisco, and at Commonweal Institute to make this research happen. And I think it’s also important to say this study was funded primarily by Friends of the Earth members, as well as some grants from foundations, and no funding was taken from any companies or any industry players.

TM: Kendra, you know, this is only one of many studies. And there was another study that was released, I think, just before this one, and I’m sure you’re familiar with it, and it came out of France. It went from 2009 to 2016, like seven years. They used 68,946 participants. I think they found that the people who were on organic diets had a 25 percent reduction in cancer.

KK: They did. And these studies together, along with a growing body of studies that are trying to understand the benefits of organic, paint a really important picture. Our study was looking at exposure, so we weren’t looking at health outcomes. That is a more complicated thing to do and, like the study you were referring to, takes years because our exposures to pesticides or other concerning chemicals may take years to manifest in negative health problems. So we looked at exposure. What we found is an organic diet can dramatically reduce exposure.

Studies like the one you’re talking about, and there have been others, look at health outcomes. So how can switching to an organic diet improve our health? And what they found, as you said, for the participants who reported eating the most organic food, there was a 25 percent reduction in incidence of cancer. And there have been other studies like this that have found fertility benefits for women who report eating organic, as well as a reduction in diabetes risk for people who report choosing organic. And so all together, what these are telling us is, first, that we can reduce exposure to pesticides by choosing organic; and second, that that can lead to some great health benefits.

And this is why, at Friends of the Earth, we’re really putting this in the context of how do we create a food system where organic is for all? Because really, if you think about our daily exposure to pesticides through the food we eat, we could consider that a form of toxic trespass. It’s not something any of us asked for or consented to, and it shouldn’t be up to us as individuals to go and shop our way out of those exposures. And we know that many people can’t necessarily afford organic food or even the healthiest food in the grocery story on a daily basis.

And so we’re working very hard to reframe this issue as organic as a human right, because we all have the right to food that is free of toxic pesticides. And then when we look down the supply chain, farmers and farm workers have a right to not be exposed to pesticides that lead to increased rates of all sorts of health problems in those populations, in rural communities, in the kids of farmers and farm workers. And so we are working with many allies to not only advance market-based solutions and public education but to change the policies that set the rules of the game.

TM: Well, you know, Kendra, I know that you’re very familiar, because you’re the one that told me about this 18-year-old study that was done in Salinas Valley with farm workers, called the Chamacos Study. And wasn’t there some rather chilling results?

KK: Yeah. So Chamacos is research being done out of UC–Berkeley, and one of our co-authors, Asa Bradman, also is a researcher on that project. And they have been tracking rural children in Salinas since they were born—or before they were born, actually. They enrolled 200 pregnant women and have been testing their bodies for exposure to pesticides. And one of the classes of pesticides they really focused on are organophosphates. Like I mentioned before, chlorpyrifos is one of those.

TM: Can you say just a little bit more about what organophosphates are, just for our listeners out there who might not really understand what those are?

KK: Yeah. Organophosphates are a class of pesticides that are related to sarin gas. They’re nerve agents and they’re highly neurotoxic. So what the Chamacos Study has found, and other studies, is that exposure to organophosphates increases risk of reduced IQ, autism, learning disabilities, motor skills, other things associated with the nervous system and the brain. There are a group of researchers who recently put out an analysis that called for a full phase-out of organophosphates because there’s enough data that shows that we should be concerned.

And again, this really backs up the importance of shifting to an organic food system for all of us, all along the supply chain, because we’re using really toxic pesticides to grow our food. And they have the greatest impact on those rural communities.

TM: Well, you know, there’s a ton and ton of talk constantly about glyphosate in the news. And you don’t often hear about organophosphates, which are much, much worse. And of course a lot of people are saying get rid of glyphosate, get rid of glyphosate. Well, glyphosate is going away because they overused it and now we have superweeds. But I just am thinking about an article—and this was the first I heard of it—just last week which said that the new cocktail that is Enlist Duo also includes dicamba, 2,4-D, and glyphosate, also now have superweeds. So, you know, this is about a pesticide treadmill that we’re on. How do you see us dealing with this constant new pesticide, now new bugs and new weeds that are now resistant to it, and this is going on and on? Are we going to ever get off this treadmill?

KK: Wow! In my hopeful moments, I think… I think that we have to. And I hope that people… There are so many issues to pay attention to, and we’re all really flooded with bad news all the time. And so I think it’s hard to inspire people to take action. And I hope that knowing that there’s a real solution and that organic works can inspire people to fight for an organic food system, because that’s what it’s going to take, is a change in policy. And we will need thousands and maybe millions of people working to make that happen. I think, until we have regulations that phase out the most toxic pesticides and that support more and more farmers to transition to ecological farming methods, we will be stuck on this pesticide treadmill. And part of why we do this work is to educate people and to inspire them to get engaged to make that change.

(23:29)

TM: Well, and Kendra, you do a lot of policy work too, which… We subsidize corn now and soy and those very heavily pesticide crops, corn being the worst. What if we moved some of those dollars in our policy—in our policies, and especially the Farm Bill and other policies and state policies—towards organic systems that significantly reduce, as you’ve shown in many of the studies… What do you think some of the steps are that we could do to see if we can’t move that policy in the right direction?

KK: Well, the biggest piece of policy we need to change is the Farm Bill. And that’s negotiated every five years, and it really determines what food we’re growing, how we’re growing it, what’s available to us as eaters. So we were involved in the Farm Bill last year—that’s the last Farm Bill that was passed. And what we saw does give me some hope that there is… What we saw is that there’s bipartisan support for organic farming. And we did have some important wins around organic in that Farm Bill. We had an increase in research funding for organic, an increase in the funding for the National Organic Program itself and improving its ability to monitor and regulate organic. But it’s still pennies. It’s still just a drop in the bucket compared to the billions that we are funneling toward the pesticide-intensive system. So absolutely, we need to turn that on its head.

And I think what’s really important, from my perspective, is not that we make organic food cheaper, because the people who will get squeezed then are farmers, and we need organic to be a good livelihood for farmers. What we need is possibly subsidies that support farmers, and that could bring down the price of organic in a way that’s sustainable for farmers. But also really, from a systemic perspective, what we need is a livable minimum wage so that everybody can afford healthy food for their families. It’s not only that people can’t afford organic—it’s many, many families in the U.S. that can’t afford food on a steady basis. And so if we created a truly fair system where everybody could feed their families, then more and more people could choose organic.

TM: Well, I’m really, really glad, Kendra, that you’re bringing up the social issues. There’s an article, I think, that was co-written by one of your colleagues, Kari Hamerschlag, on the Green New Deal. And in it I really was impressed with the way that she approached it: just that we need social justice as well as environmental justice. And of course, social justice is economic justice as well. Do you see, if we are going to make this change in the next 12 years—apparently we’ve been sort of handed by the United Nations a dire warning: Change in 12 years or else! How do you think that we can facilitate or enhance or encourage change a little bit faster than what’s happening now? Do we really have to wait another four years before we go after the Farm Bill again?

KK: That’s a great question. Right now I think the Green New Deal is a really important opening and opportunity. There’s a lot of momentum behind it. And we are working to get agriculture included because it hasn’t been front and center, even though the agricultural sector is a leading source of greenhouse gas emissions and could also be a leading solution. So we have been working to make that part of the conversation and ensure that whatever policies come out of this momentum around a Green New Deal includes agriculture and shifting toward sustainable agriculture as parts of that effort.

TM: Well, it seems to me that we have solutions. I really, really appreciate the work you’re doing, Kendra, and Friends of the Earth. You are showing a solution, and I am thrilled that you are sticking with your number one principle and that you’re being bold and fearless. And also, Kendra, if those listeners out there want to donate to Friends of the Earth, you have lots of people who give small donations, don’t you?

KK: We do, and that’s really how this study happened, was the generosity of our members. And small donations all add up. So people can go to OrganicForAll.org or FOE.org to do that.

TM: So, Kendra, thank you once again for all the great work you’re doing and for being an inspiration to us all.

KK: Thank you so much, Theresa. I was so glad to have the opportunity to talk to your listeners.

You can listen to Rootstock Radio on the go wherever you get your podcasts, and find us online at RootstockRadio.com. Rootstock Radio is brought to you by Organic Valley.

© CROPP Cooperative 2019

Related Articles

- Tags:

- pesticides & herbicides,

- organic nutrition,

- organic & sustainable living,

- Rootstock Radio,

- women in food & agriculture