Organic

The Man Who Wrote the First Organic Standards

Harry MacCormack has spent nearly half a century—45 years to be exact—farming organically at Sunbow Farm in Corvallis Oregon. And although that in itself is accomplishment enough, it’s just the beginning of Harry’s list. Harry is the co-founder of the organic certifier Oregon Tilth and served as its executive director for many years. Additionally, he is a founding member and the current president of Ten Rivers Food Web, a retired Oregon State professor and the author of eight books.

Harry grew up in the (then) small farming community of Chenango Bridge, New York, where he observed first-hand the industrial agriculture takeover. “It went from that kind of self-sustaining community: interactive, everybody knowing each other, to—as soon as the freeways were put in by General Eisenhower—we had the first box store show up down closer to Binghamton [NY], and it was within a couple of years most people had stopped gardening and were buying from the store.” Later, when Harry’s family moved to California and settled in what would later become the Silicon Valley area, he saw a similar phenomenon. “Another thing that really changed my consciousness was watching how fast you can change a major food production area [like the once-lush Silicon Valley] into the cement jungle that it is today.”

These and other formative experiences led Harry down a remarkable path. “Yeah, I actually wrote the first organic standards and it’s kind of funny how it happened,” he says nonchalantly. Turns out, the first organic standards came as a byproduct of bed-rest mandated by Harry’s chiropractor after he hurt his back moving manure. (For full details listen to the episode!)

Of the first standards themselves, Harry says they “sat down and scratched out some preliminary stuff,” and that the first organic standards “were all a stand-off against chemical corruption, corruption of the soil and the air and the water. And we didn’t have any rules to play by.”

From today’s perspective, fighting the corruption of our environment was a pretty good place for Harry and his colleagues to start.

Listen to the rest of Harry’s story, hear about his current project(s) and hopes for the future at the link above, on iTunes, Stitcher, Google Play or wherever you get your podcasts. And don’t forget to subscribe to have the dulcet tones of Rootstock Radio served straight to your ears every week!

Welcome to Rootstock Radio. Join us as host Theresa Marquez talks to leaders from the Good Food movement about food, farming, and our global future. Rootstock Radio—propagating a healthy planet. Now, here’s host Theresa Marquez.

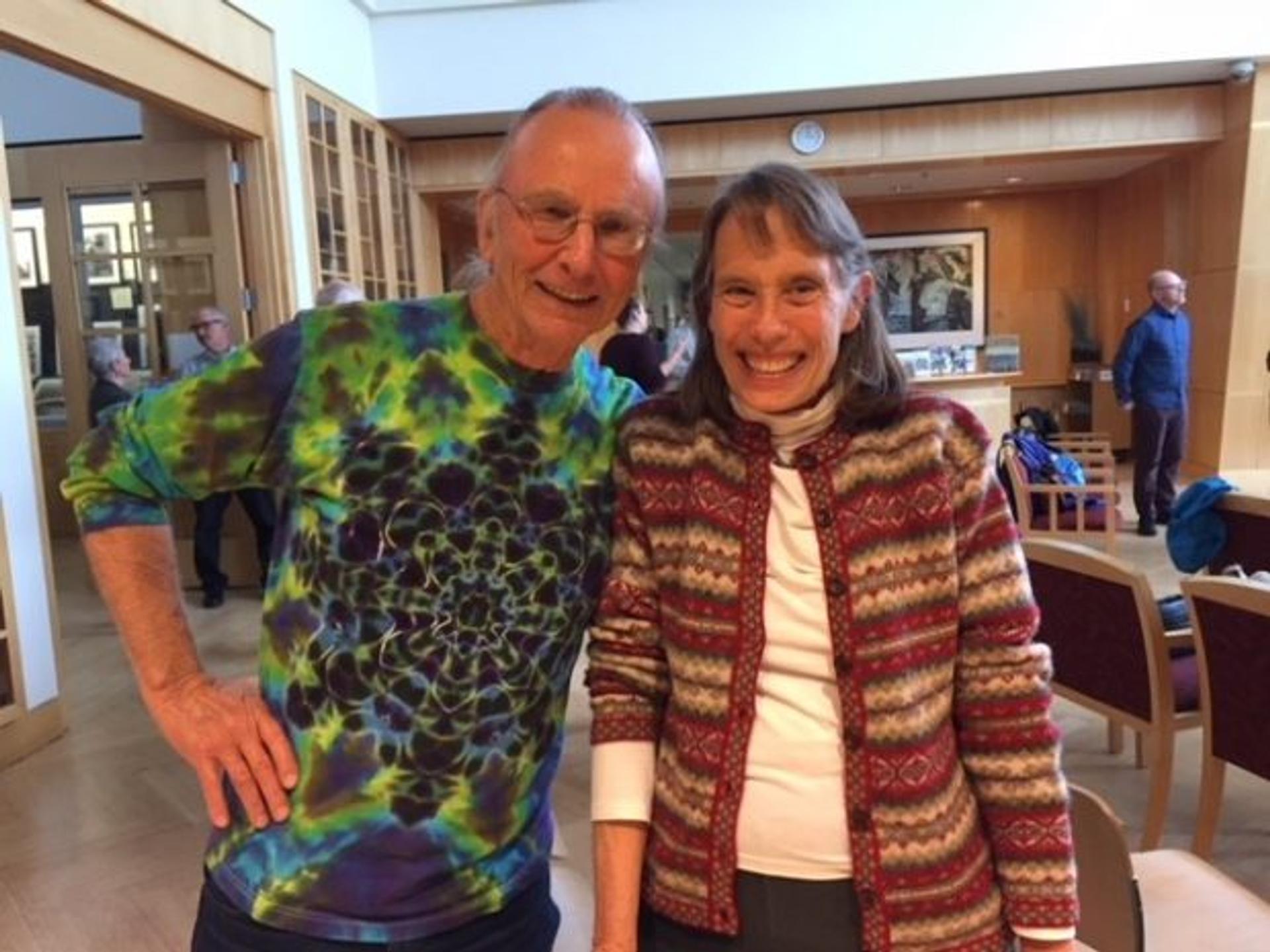

THERESA MARQUEZ: Hello, and welcome to Rootstock Radio. I’m Theresa Marquez, and I’m here today with Harry MacCormack. And it is so fun to try and describe Harry, but I’m going to start by saying he’s an organic farmer for 45 years—in fact, probably one of the first organic farmers in Oregon—but I think that Harry is much more. He’s a writer, he’s a poet, he’s an activist, he’s a writer of certification standards. And I think at heart he’s probably a rebel, and definitely part of the alternative agricultural movement for many, many years. Welcome, Harry!

HARRY MACCORMACK: Thank you.

TM: I hope you don’t mind me calling you a rebel.

HM: That’s fine. That’s exactly what I am.

TM: That’s so wonderful. As I look through your history, you have been unquestionably at it since probably you were young. In fact, I read that your grandfather was a horse farmer.

HM: Yes, Russell Yager, outside of Oneanta, New York. He had Percherons. I only knew him as a very young kid and he was pretty much retired from farming at that point. One of his sons—but anyway, somebody else had taken over the farm. I actually have pictures of those horses that I value.

TM: So would you say that—you and I are both kind of like 1960s kid, so we were wired to be rebels—but would you say your parents got you into this passion for our ag and food?

HM: Yes, I grew up Chenango Bridge, New York. My dad was one of the people who put IBM together and that was Endicott, over the hill. But we lived in this little rural community and we grew all our food because it was World War II, and the rest of the community supplied the rest. Mr. Terrell(?) did chickens and somebody else did beef and veal, and it was like that. I just grew up doing that as part of our process. My sisters, the same way, and we still both try to grow a bunch of our own food, and that’s where it comes from.

And then the other perspective that really informed all my work was experiencing that shift right around the Korean War where that community suddenly—looking back it was like overnight—it went from that kind of self-sustaining community, interactive, with everybody knowing each other, to, as soon as the freeways were put in by General Eisenhower, we had the first box store show up down closer to Binghamton, and it was within a couple years, most people had stopped gardening and were buying from the store.

TM: Yeah, it’s amazing isn’t it, to see how we took the healthy activity of feeding ourselves and decided to let someone else do it for us. I was also curious about how you ended up in California, and then you went back to New England and went to college again, and then you moved to the Midwest to college again, and then back to Oregon. Tell us about your journey.

HM: My dad, I mentioned, was one of the developers of IBM. His gold disk pack, if you look up the patent on that, was the memory unit for the big mainframe computer. So he had a lot of patents. But he was one of the early guys in that whole thing, and when they sent him to California—I never knew this until after he passed, actually—he actually sited the plant in San Jose, which was the third plant. So we got a call from him—we were told to start packing stuff up, we were moving to California. They say 3,000 families a week [were] moving into the Bay Area at that point. And what became Silicon Valley replaced all those beautiful—it used to be called the fruit basket of the world. And that’s another thing that really changed my consciousness, was watching how fast you can change a major food production area into the cement jungle that it is today.

TM: Well, they’re still producing a huge amount of food. In fact, there are some things that they’re the largest producer of—so many of the fruits and veggies, avocados, and things like that.

HM: A lot of that moved over to the Big Valley and other places in California. The whole structure of that valley changed, and the focus became strip malls, freeways, and Silicon Valley. It’s just what we see there today—yeah, there’s some food production there, but it’s nothing like when we moved there. When you stood up in the Santa Cruz mountains and looked over that valley back in the 1950s, all you saw was orchards.

TM: So, Harry, you have been such a pioneer in organic. What got you up into Oregon and doing an organic farm?

HM: Well, when I was a kid in San Jose and I was a teenager, I became president of the San Jose Youth Presbytery. Not by my own choosing, actually—the kids in the group pushed that, and they had told me to get over the hill and to Santa Cruz because I’d just been elected this office, which covered everything from San Francisco down to Fresno.

So that was my first shot at being somebody that had to take on a leadership role. And in that position, I became friends with and listened to mentors who were in the Presbyterian Church but were men that were in the civil rights movement and stuff like that. And I actually was accepted at Occidental, but I had gone to L.A. to a conference and couldn’t stand the smog in my eyes. And Lewis and Clark College in Portland, which was much smaller than it is now, then, offered me enough so I could go there as long as I kept working.

And I came to Oregon and went there for four years. I have to say that the journey here to this beautiful state immediately gave me the feel that I had as a kid in upstate New York, and it was a totally different feel from what I’d felt in the Bay Area of California. So I made a decision, really, while I was going to school there that I was going to do everything I could do to live in Oregon somehow.

And I’ll tell you, when I graduated from the Writer’s Workshop at the University of Iowa, I was offered jobs all over the Midwest. And I declined all of them and took what was considered, in those days, a kind of junk job at Oregon State University, where I stayed for 31 years and developed this farm and did my life.

(7:33)

TM: Well, you know, Corvallis is just, in that whole area, is just a wonderful—

HM: It’s a bubble!

TM: Yeah. I’d love to go back and just talk about how Oregon Tilth came together. A lot of us, just so that we can get this acronym out of the way, called OTCO, Oregon Tilth Certified Organic. And Harry was the first executive director and has been a pioneer in organic. And in fact, Harry, didn’t you have something to do with writing the first organic standard?

HM: Yeah, I actually wrote the first organic standards. It was kind of funny how it happened. I hurt my back while moving manure, actually. It was semi-composted manure from the fairgrounds, and my back went out. And so I was confined by the chiropractor, he told me to lie down—and if you know me, I never lie down. So he told me to lie down for a couple of weeks and that I had to come in every week for six weeks and he’d get it fixed, but it was pretty serious.

So here I was on the couch—we had been talking about doing standards in the Oregon Tilth framework at that point, which was extremely young, and we had to go back to Regional Tilth, which covered all of Cascadia, over into Montana and Idaho. And [unclear—regionally?] in Oregon, especially in the Willamette Valley, had started a little fledgling certification program. Bob Cooperrider, who was a valley farmer just up north of us, actually wrote down the first, what we would call, I guess, some kind of a standard for organic. And it was one page, and there were 12 of us that signed onto it. And the game at that point was, each of us had to be a certifier, so that looked kind of like an agent to go out to a farm and certify somebody’s else’s farm.

TM: Harry, can I back up though, just for one second. Because while I’m interviewing pioneers, it just strikes me over and over again that the farmers are the ones that really wanted this standard.

HM: Yes, yes.

TM: And they wrote it, and they didn’t care if it was going to be an industry. Tell me a little bit about why do you think everyone became very passionate about, “We have to do organic” Just so that we can get, kind of, grounded in the “why” here.

HM: Well, if you look at the first standards that I wrote, which will be archived in the OSU library, they were all a standoff against chemical corruption—you know, the corruption of the soil and the air and the water, which we’re still dealing with. But we didn’t have any rules to play by. We had the stuff that was coming out of Rodale to kind of direct us a little bit, but we didn’t have any rules. And people like Bob, who was growing, at that time, not just fruits and vegetables but he also had gotten into a little bit of grains, he was actually shipping, and people wanted to know what he meant by organic.

So we sat down and scratched out some preliminary stuff. And I have to say that those first standards were kind of like reading Rodale magazine; they were based on philosophy and what we believed. And we believed that the planet should work in a certain kind of way, and we didn’t want that to be corrupted by various kinds of chemicals and other parts of industrial agriculture. So that was what we started with, and then there was a second version of that that Lynn Coody got involved with—my cofounder of Oregon Tilth, along with Yvonne was involved in that too. But the second round was me and Lynn, and we are the authors on the second version of the Standards and Guidelines for Organic Agriculture.

And she brought to it her degree in biology and her sense of incredible order, which I love. (Laughing) The only reason why we have a history of Oregon Tilth to give to the libraries is because she kept all of it very—

TM: She is amazing!

HM: She’s just amazing, yeah! The two of us together are kind of an interesting force.

So that became the basis that then Yvonne Frost, who passed away a year ago, Yvonne picked that up as a business woman who had a sense for what could happen in the world, and took this little fledgling certification program and looked at it as a business. And part of what she and Lee Fryer, who is another old, old influence on us, the two of them had this vision that I actually didn’t share—and I don’t know if Lynn did either—but the vision they had was let’s have organics in every store in the country.

So she came with this notion of, okay, it’s good to certify the farms, but we’re not going to make any money doing that—which is in fact still true. Where the money is going to be is in taking the stuff from those farms as it goes to processors and certifying the processors, and that’s how it’s going to get in all the stores. So Yvonne Frost, and there was another Yvonne whose last name I forget in Minneapolis…the two of them are the—they were both older women. They were like, I think Yvonne was 10 years older than me all the time. They were the two that kind of took it to that next level that was necessary to… And then we had to come along and write standards and guidelines. So we had these incredible meetings. I remember one at Davidson’s up in Tualatin where we had the Sikhs from Kettle Chips there—

TM: Golden Temple Bakery, yeah!

HM: Yeah! And we had Gene Kahn from Cascadia—he was one of the primary organizers of all this stuff. And Lon Johnson, whose name’s different now, Trout Lake Farms—

TM: Yeah, Trout Lake Farms, and I think he’s in China now.

HM: Yeah. And so there were these pioneers. And I remember sitting in that room, and it was a glass room on the side of the restaurant—one of those kind of rooms. And people would come in, in the parking lot to go to the restroom, they saw these Sikhs sitting there with their headpieces on, and their eyes would get real big and they’d stare in the window at us. That’s what we were doing; we were sitting there, we were actually sitting in that meeting trying to figure out how to do processing standards because nobody had ever written them.

TM: And what year was that, Harry?

HM: That probably would’ve been around 1987–88, something like that. I’m just looking at the…I’ve got the transition document sitting in front of me and the first copyright on the first part of that book was ’88. Of course, I rewrote it a bunch of times after that.

(14:28)

TM: If you’re just joining us, you’re listening to Rootstock Radio and I’m Theresa Marquez. And I’m so delighted to be here today with organic pioneer Harry MacCormack, organic farmer for 45 years at Sunbow Farm, Corvallis, Oregon; co-founder of one of the oldest certification organizations in the country, Oregon Tilth; and a founding member and current president of Ten Rivers Food Web; author of eight books. Wow, Harry, you sure keep busy, don’t you?

HM: Yeah.

TM: It is wonderful to hear about these early days of Tilth. And so, you know, when you said 1987 to ’88, that was two years before the standards.

HM: Yes. And what we were doing at that time, in ’89 and ’90, and probably ’88, ’87 maybe, I don’t remember the exact dates on this. But Yvonne—again, Yvonne Frost, in her perspective and what she did…and she was working with Gene and Lon and other people on this, and then working with the people in California, and we formed the Western Alliance. So that was an attempt to pull together CCOF [California Certified Organic Farmers], Oregon Tilth, and what was the fledgling program up in Washington because the farmers up there couldn’t get anybody to agree to anything so they actually went to the state. So the Washington State Program was either the first or the second in the state, I think, in the United States. I think Texas might have been the first, and that one was based on our standards. Both programs, those states programs used our standards to get going.

So we would meet usually around Ashland. The people from California would drive up and the people from Washington would drive down. And Yvonne would rent a big car, like a Cadillac or a Lincoln Continental, and there’d be like four or five of us crammed in there, Dr. Alan Kapuler being one of them. We’d go down and spend two or three days standing there in a—there was a motel down there that had a really nice conference room. Lynn was there. We were doing science, trying to figure out how to create standards that weren’t based on philosophy. So that’s how we came up with what, in my mind, I think, became the basis of the national standards that are based on materials.

TM: Yeah, and all the other many, many dozens of state and private certification organizations. It’s interesting that we talk a lot about how organic went from a movement to an industry. And I’m now realizing, it went from a philosophy to trying to be more science based. But wouldn’t you say the philosophical roots are probably just as important as the scientific ones?

HM: Oh, they’re totally important. That’s one of the reasons I wrote the Cosmic Influencesbook. I just had, last week, a group of 17 third-graders from the Waldorf school here out on the field. If we go back and look at who the real pioneers were, there was Rudolf Steiner and, what’s her name there in England…those people influenced Rodale. Rodale influenced all of us with their publications. So, it goes back to the ’20s and ’30s, really. We’re carrying that philosophy still.

TM: Congratulations, I will just say, for all the good work that you’ve done for organic. Without you, Harry MacCormack, and so many others in the farming community who were so dedicated to wanting to do something different and were so strong about it, we wouldn’t be in organic today. I often tell people in the business community, you know, the people who started didn’t care if it was a business or not. They wanted a business, but they were more interested in making sure that we were doing the right thing.

So if we fast-forward just little bit, how about, what is Ten Rivers? Tell us a little bit about that.

HM: So Ten Rivers Food Web was put together in that period in the time around 2004–2005 where, for whatever reason, the vibe in the community was food security. So there was a whole notion around the country. There were a lot of food security committees set up; Eugene had one. Ours here started with an open mic forum that had about 200 people at it. After that we had a series of meetings that involved, a lot, the faith community, which is another whole part of this thing—people that believe in doing things right; it’s a moral thing.

So we got together, and there was one point at which we were sitting in the room at the coop, in the meeting room, and Sharon Thornberry—who’s famous all over the country and has ties, like I do, with Native American people—we got everybody to visualize standing on top of Mary’s Peak, which is the tallest mountain in the Coast Range and is just west of our farm. The Native people call it tcha Timanwi [frequently anglicized to Chintimini], “Place of the Spirit.”

So, from the top of that mountain on really clear day you can see all the way to Washington and all the way to California. And we were trying to get people to stand up there in their minds and visualize what it was we were talking about as the area that had to be connected through food. And that notion of a bioregion supporting the whole food web—and I’ve got a design of it sitting in front of me here that starts with climate, water, food land, plants, animals, living soils, insects and microbes, the waste recovery system (which people don’t think about), nutrition, humans and our impact, distribution markets, and food preparation. So we put this organization together to deal with all of those as an interactive web and a way of kind of transforming a community notion of how we support each other and how we support farms and how we support processors and all that.

TM: You know, Harry, as we look at a rather failed democracy—goodness knows how to even describe what’s going on nationally in our government—I think many of us are really, really more interested in this idea of bioregionalism. Both because it includes not just the environmental ecological, but also how we work together, communities. So I’m very excited about—there’s so much that you’ve done, but now this idea of becoming a model for bioregional. Is that how you see the Ten Rivers? How do you see some of the work that you’re doing could maybe get pushed out and be seen more as a model and maybe adopted across the country?

HM: So, just to tell you the really exciting stuff that’s happening daily for me: I’m sitting here looking at a computer that’s got, of all things, notes from about six or seven engineers from all over the country. And why would I be looking at that? Well, when you look at waste recovery—which, I own a compost business here on the farm, so I’m doing waste recovery, because what I’m doing is taking what used to go to the landfill, mainly leaves from the city, which they’ll start delivering in about five weeks, and I make them into compost. So I’ve got vegan compost. That’s one level of waste recovery.

What’s gotten really exciting in the last year is we were looking at our web, and food distribution, as we’re seeing with the Puerto Rico thing, is key. You can have food sitting there, but the distribution is what’s key. That involves trucks. Trucks are diesel. Diesel puts all kinds of pollutants into the air that we don’t want to breathe. So we started thinking, wonder if we could get these trucks to run on some kind of alternative fuel? And we started working with Organically Grown co-op in Portland, which is the big northwest distributer—one of them—and we started working with Pacific Fruit. And we started talking to both of them about, how about we work on a project to transfer all these trucks over to hydrogen eventually, which would give zero pollutants. And somehow, we do that with, kind of, the waste products—which there’s a number of them—that come from the system that we’re a part of here locally.

So that project has gone head-over-heels forward. We have people from all over the country involved. And the first recovery plant’s going to be in Centralia, Washington, probably within six months.

TM: Fantastic!

HM: We’ve got another one over here at Linn-Benton Community College, which will involve training kids to be the engineers to do all this stuff. But this is the basis of community, is fuel and food. And we can organize the whole community and jobs and everything else around that in a way that’s supportive of everybody. And we’re targeted on rural communities because most of Cascadia is rural, and we have urban centers like Portland, Seattle, and smaller ones like Eugene, Salem, and Olympia. But when we’re talking most towns here in the northwest, we’re talking—and even in the Midwest—we’re talking under 50,000 or, for USDA fuel purposes, we’re talking 150,000 or under.

So we’re talking about all the people that live in that area. Some of them are producing food, but everybody’s using food and other parts of the ecosystem and generating waste products. And we can make those into things that will support that system. We don’t have to have landfills. And that’s part of the food web!

(24:27)

TM: The food web. And also, as our listeners will know, I’m always saying we have so many solutions for our problems.

HM: Yes, we do.

TM: Whatever problem we have, we probably have a very, very ecological and community solution.

HM: And the technology is out there! I mean, we’ve got our organic technologies that we know work worldwide now. We didn’t know that when we started all this. But we know, we have data that shows that these systems work, and we don’t have to be dumping chemicals everywhere. We have systems that are already created, and all the testing’s been done on them. We don’t need to be addicted to fossil fuel in anyway.

TM: Yeah, either in chemicals or other things. Before we forget, I want to make sure, www.TenRiversFoodWeb.org. If you log onto that, you can hear more about the Ten Rivers project. Harry, are there other websites that you would like to recommend to our listeners?

HM: Well, the Sunbow website has my books, so SunbowFarm.org.

TM: SunbowFarm.org. Well, Harry, I know that you have a book in the works, that you’re very, very active with Ten Rivers Food Web. I look back at our 40 years of being in this industry, or in this movement that became an industry. What do you see that you feel is really helpful about what’s going on with organic now?

HM: Well, I think you and I both know, if we hadn’t made the move to put the national program in in 1990 I don’t think it would ever have happened. And it only happened by one vote in the House and one vote in the Senate, so thank you, Peter Defazio and Senator Leahy. If it hadn’t have been for those two guys, we wouldn’t have a program. And thank you again to Lynn Coody for standing there with Peter Defazio and describing to people what it was that were trying to do. She stood there on the House floor with him.

And fortunately, we put that groundwork together when it had to be put together. And what we have to do carrying forth, I think, is keep the expansion going. We have to somehow find mechanisms to allow these younger people who want to farm to be able to be on land, because the price of it has gone out. It just keeps going up. And we have to find creative ways to get that land out of this spiraling market thing, because it just can’t be held that way, where at any point somebody can sell the land out from under a farmer, or the farmer themselves might sell it out. We see all the time—we had 340 acres last year suddenly, because, well, whammo, somebody who held the lease, that 340 acres of organic grains became chemical overnight.

So we have to secure the basis of the food that we’re growing. Our farm is set up with a family trust and corporation that includes the people that are farming it, so it took a lot of legal work to that. There’s various ways to do it, is the point. But that’s got to be one of our focuses, is that we’ve got to focus on food land, what’s necessary to feed people a high-quality diet, and then make the mechanisms available that can take that into a future that’s very uncertain in a lot of ways.

TM: Harry, thank you so much for that thought, because we do want to keep every acre in organic. And we want to keep even conventional farmers, we want to keep every conventional farmer and organic farmer and sustainable farmer farming. So, thank you so much, Harry, for talking with us today, and I’ve just learned so much from you and I’m so inspired.

HM: Yeah, you know—I mean, I’m 75 yesterday and I don’t see any change that’s going to allow me to get out of this. I tried to step down as president of the board of Ten Rivers, and the young people looked at me and said, “You don’t get to play the old guy card.” So I guess I’m there for some period of time, I don’t know.

TM: Organic pioneer Harry MacCormack. A real pleasure to be speaking with you, Harry.

HM: Alright, thank you.